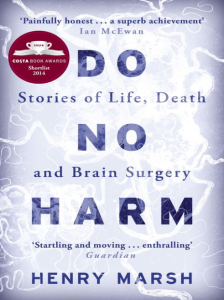

Review - Henry Marsh's Do No Harm

10 September 2015

Prof. David Sowden starts this book review section by reflecting on Henry Marsh's Do No Harm.

The world of medicine is replete with many trite, anodyne descriptive stereotypes; there is a particular fondness for negative characterisations of surgeons and psychiatrists. Henry Marsh, in this often seeringly candid and moving memoir, effectively challenges and puts a lie to these hackneyed and indolent models of surgical behavior and practitioners. Marsh shines light on a life in surgical practice in a branch of surgery that is often seen as mysterious and other-worldly even by other surgeons. However, much of this book’s ultimate strength lies in the universality of the fundamental clinical, professional and personal issues and challenges that Marsh writes about. In addition, Marsh tells a good and compelling story extremely well and with an attractive pace – something that many modern authors seem incapable of doing. Perhaps it is down to his unusual route into medicine (via a Philosophy, Politics & Economics degree at Oxford) but Marsh writes especially engagingly and in a way that should appeal to both those with a medical background and those without. In that regard his preface is telling as he outlines his wish to draw out the reality of surgical and clinical practice (the triumphs and the inevitable failures), whilst not wishing to …....undermine public confidence in brain surgeons……but…[to} help people understand the difficulties – so often human rather than technical - that doctors face”.

He elegantly outlines what he describes as the Jeckyl and Hyde-like split between the [necessarily certain and confident – who wants someone conflicted with doubt attempting such potentially life altering surgery?] surgeon in the operating theatre and the friendly, empathetic consultant who talks and cares for his/her patients, through a series of case histories/patient stories. The need to be objective and appropriately detached, whilst not losing one’s humanity and compassion, being a particular focus of Marsh’s writing.

It was particularly interesting to read of his practice of seeing patients the night before their operations and his efforts to avoid such interactions on the day of the operation so as to concentrate on the technical task at hand without the emotional distraction of personal contact. This appears to me understandable, even desirable, but perhaps increasingly unrealistic in an NHS where bed occupancy concerns lead toward ever more patients being admitted on the day of their surgery.

Throughout the book he writes with humanity and humility (there is little or no hubris here) and he is, if anything, too self-critical. He is also almost alarmingly honest about the mistakes he has made. As he emphasises, all doctors make mistakes but the key is to learn from them; but goes on to highlight that surgeons find it difficult to admit to them and that many find all manner of ways to disguise their errors. Whilst Marsh largely succeeds in one of his aims in writing his book..

He elegantly outlines what he describes as the Jeckyl and Hyde-like split between the [necessarily certain and confident – who wants someone conflicted with doubt attempting such potentially life altering surgery?] surgeon in the operating theatre and the friendly, empathetic consultant who talks and cares for his/her patients, through a series of case histories/patient stories. The need to be objective and appropriately detached, whilst not losing one’s humanity and compassion, being a particular focus of Marsh’s writing.

It was particularly interesting to read of his practice of seeing patients the night before their operations and his efforts to avoid such interactions on the day of the operation so as to concentrate on the technical task at hand without the emotional distraction of personal contact. This appears to me understandable, even desirable, but perhaps increasingly unrealistic in an NHS where bed occupancy concerns lead toward ever more patients being admitted on the day of their surgery.

Throughout the book he writes with humanity and humility (there is little or no hubris here) and he is, if anything, too self-critical. He is also almost alarmingly honest about the mistakes he has made. As he emphasises, all doctors make mistakes but the key is to learn from them; but goes on to highlight that surgeons find it difficult to admit to them and that many find all manner of ways to disguise their errors. Whilst Marsh largely succeeds in one of his aims in writing his book..

an increasing obligation to bear witness to past mistakes…..[and in so doing encourage his trainees to] learn how not to make [such] mistakes themselves”What is less clear is how, apart from his description of the importance of professional detachment, he himself has managed to continue to practice in a specialty where error or mistake have such catastrophic consequences without him having the fall back position of forgetting those mistakes or passing blame elsewhere. Much is currently made of the importance of resilience in medical practice, and this book is a testament to Marsh’s resilience. Unfortunately, he isn’t clear how such resilience is developed and preserved across a professional lifetime. That doesn’t lessen the value of the book but addressing it might have made the book even more insightful. From a personal perspective I would have liked Marsh to explore the nature of learning from mistakes a little more, as the key is to ensure the learning actually addresses the causes of the mistake and that a mistake, rather than mere misfortune, had actually happened; to do otherwise is as potentially unhelpful as denying a mistake in the first place. As a medical educator I well remember facilitating a workshop on “clinical/professional errors” amongst senior clinicians and being alarmed at the frequency with which many clinicians took the wrong learning from their more serious “mistakes or errors”. Perhaps the most worrying of which was the inclination to avoid, often at all costs, managing patients with similar conditions to the one around which the original error occurred. In other instances there was, in fact, little to justify the clinician’s belief that they had committed a gross and unforgiveable error; rather they were victims of clinical “bad luck” but had converted the terrible patient outcome into a personal responsibility. Similarly, it was worrying to hear that the workshop was the first time that many had ever discussed their “error(s)”, and the extent to which that unadmitted experience had blighted many aspects of some of the doctor’s lives. Marsh writes particularly well about the other worldly beauty of the living brain, in contradistinction to the lumpen sponge of a preserved brain that is seen so often on TV or in pathology specimens, and was an all too familiar feature of dissection as a medical student. Indeed it is the quality and clarity of the language and the pictures he paints that make this book a genuinely enjoyable read despite some of the more difficult content. Content that on occasions creates the all too common sense of there but for the grace of god go all of us in clinical medicine.

The book has many brief but considered reflections that should give any practicing clinician pause for thought and as is so often the case the sum of the parts is exceeded by the impact of the whole. The following 2 examples give a flavour of the wider themes that Marsh visits during his exploration of his neurosurgical career, but in reality could be part of any doctors career experience:

The book has many brief but considered reflections that should give any practicing clinician pause for thought and as is so often the case the sum of the parts is exceeded by the impact of the whole. The following 2 examples give a flavour of the wider themes that Marsh visits during his exploration of his neurosurgical career, but in reality could be part of any doctors career experience:

..wondered, yet again….. at the way we cling so tightly to life and how there would be so much less suffering if we didn’t. Life without hope is hopelessly difficult but at the end of life hope can so easily make fools of us all..And

… I felt shame, not at my failure to save his life – his treatment had been as good as it could be – but at my loss of professional detachment and what felt like the vulgarity of my distress compared to his composure and his family’s suffering, to which I could bear impotent witness.”Is this book worth reading as a busy clinician? – My answer is a definite yes. I think it will be as rewarding a read if read over a short period or chapter by chapter in a snatched moment at the end of a busy working day/week. Is it a great book in this genre? – Possibly not great but certainly very good indeed. Oliver Sack’s works such as Awakenings and A man who mistook his wife for a hat may offer a more demanding read and a wider philosophical perspective but that has to be balanced by the fact that they are not as approachable as this book. I see this as this being a particularly good book for those who might either be planning a career in medicine or specifically neurosurgery, or indeed surgery more generally; though I somehow doubt that you could pick out some of the key nuances and the precision of some of the vignettes without a deal of clinical experience. If you want to hear Henry Marsh talk then you can still hear him on The Life Scientific (30th June 2015 edition) by accessing the Radio 4 website. If you enjoyed this book then Atul Gawande’s book Complications (a surgeon’s notes on an imperfect science. 2004) is worth looking at. Gawande writes as someone who was embarking on a surgical career. The comparisons between the works are interesting and worth the effort, and the perspectives have telling resonances. Postscript – there are some telling critiques of the “new” management culture in the NHS but I am still wondering how Marsh managed to retain a personal NHS secretary for his 27 years as a consultant!! Do no harm: stories of life, death and brain surgery. Henry Marsh 2014. ISBN 978-1-7802-2592-0 Published 2014.